| It’s difficult to visualize a time when the American media didn’t yet exist in the form it takes today, constantly churning and endlessly updating with a reach so pervasive it’s nearly impossible to avoid all of its headlines and news feeds.

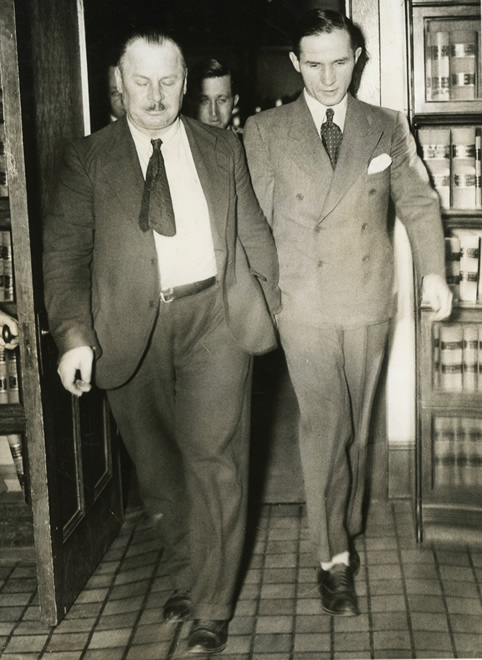

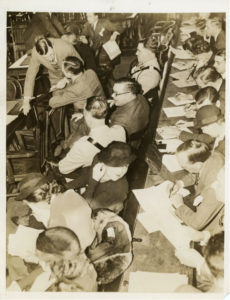

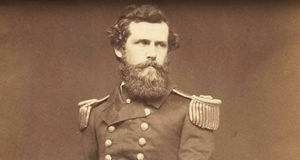

That time did exist – more than 80 years ago. In the 1930s, the media was just beginning to evolve into its current frenzied form. But the 1935 trial of Bruno Hauptmann for the kidnapping and murder of Charles Lindbergh, Jr. – better known as the Lindbergh trial – arguably kicked that evolution into high gear. News coverage of the Lindbergh trial was at the forefront of a new kind of journalism, expanding the media’s role, reach, and influence more than ever before. Reporters, photojournalists, and newspapers captivated the public with their narrative of the Trial of the Century, and the public in turn was captivated by every detail. The unprecedented coverage turned the event into a national sensation and extended the media’s influence into the courtroom – and the American judicial system. The “Trial of the Century” is captivating to our Foundation in part because of its historic role in shaping the American media and the kinds of stories it tells. But it’s also captivating to us because it is a piece of our own local history. Bruno Hauptmann was held and tried in Flemington, right here in Hunterdon County. His trial – and the media whirlwind surrounding it – reminds of us that local context is an important element of every story…even when it seems like the far-reaching media has covered every last detail there is to know. This Showcase This month we are featuring a collection of original press photographs from the Lindbergh trial. The photos, with accompanying captions, were shared with us by fellow Hunterdon County resident David Reid and were originally the property of Reid’s grandfather, Harry McCrea. They exemplify how skillfully and intently the media worked to provide pervasive coverage of the trial, fleshing out the story with pointed words and crisp images. Why were the photographs in Mr. McCrea’s possession? Because he was the warden of the Hunterdon County Jail at the time of Hauptmann’s detainment and trial in 1935. Hauptmann’s cell, set apart from the others, was only a few steps away from the warden’s desk. As warden, McCrea had unique insight into the trial. He was responsible for receiving and reading Hauptmann’s “fan mail” and monitoring Hauptmann while in his cell. Most interestingly, McCrea’s residence in an onsite apartment gave him and his family unique access to Hauptmann. One morning during the trial, McCrea’s daughter, Dorothea (Mr. Reid’s mother), came to visit her father with her toddler son in tow. Breakfast was being served, and Hauptmann’s cell door was ajar. Hauptmann, who had been watching her son play while she visited with her father, asked if he could hold the boy. Dorothea agreed, and then watched, transfixed, as her son sat on Hauptmann’s lap. For years after, she would remark to family that she “didn’t understand how he could have killed anyone. He was such a nice man.” Dorothea’s opinion echoes little to none of the media’s coverage of the trial, as Hauptmann’s guilt was barely called into question. Not surprisingly, he was eventually convicted and executed in 1936. Yet the McCrea family’s unique role in the trial and fascinating oral history hint at the complexity of this historic trial, its defendant, and its story. Whether or not Hauptmann was in fact guilty of the murder of Charles Lindbergh, Jr. is not for us to say. But we’re captivated by the ability of the press to produce such extensive coverage – and really captivated by the ways in which local history can expose the limits of that coverage, even at its most endless! We extend our thanks to David Reid and his family for sharing their collection of Lindbergh trial photographs and ephemera with us. Our mission to preserve and share local history would not be possible without our community’s great generosity. |